Pre-K Takes Flight: Finding the Math Inside a Paper Airplane Study

I teach Pre-K in a private school in Jamaica Plain, a neighborhood on the outskirts of Boston proper. The school currently serves 160 children from preschool through grade 2, with plans to expand by a grade level each year through grade 6. My Pre-K class has 17 children from JP and neighboring towns.

Before joining this school, I worked for 4 years in a Reggio-inspired school in Modena, Italy. Listening to children and viewing them as competent co-constructors of knowledge are central tenets of the Reggio approach, and ones which I hold onto tightly in my own teaching practice. Unbelievably cool stuff happens when we listen to children’s ideas.

I was fortunate to listen to one student express a deep - and unexpected - passion for paper airplanes after a weekend at home spent folding paper with her family. This child came in on Monday and announced that she would be hosting a make-your-own airplane station at one of our classroom centers that morning. I willingly obliged - despite having no skills whatsoever with paper folding - eager to see how one student’s interest could inspire others to work with paper, either in a new way or even for the first time, as this was early in the year and some children weren’t quite ready to approach such serious undertakings as drawing, scribbling, or “writing” on paper yet.

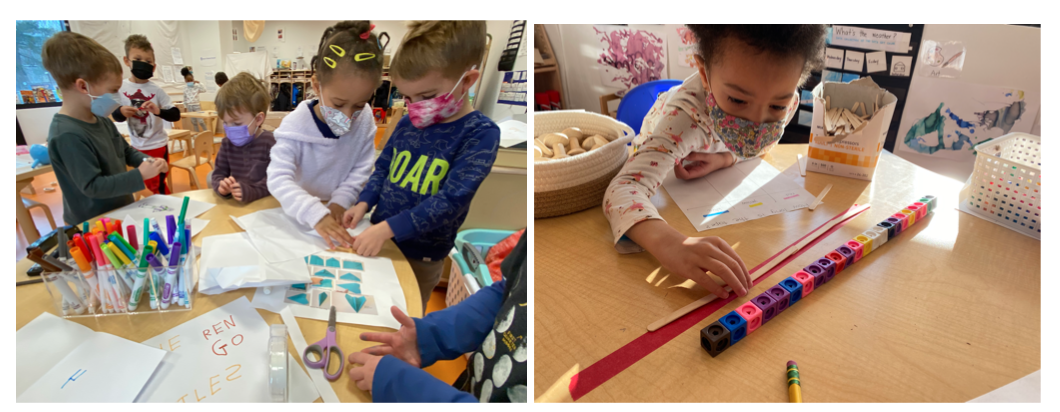

The paper airplane table with instructions and children working

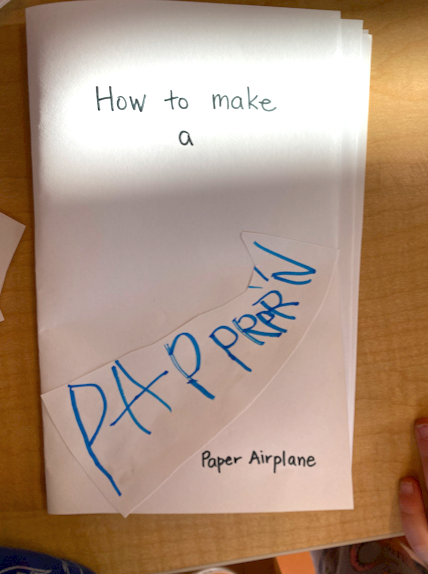

Needless to say, the paper airplanes were a huge hit. Children left the centers they normally spent all day at to come give it a try, and we, the teachers also had to sit down, study the instructions, and patiently fold and re-fold our papers alongside the children. Some children wanted to create a book explaining the steps of how to make a paper airplane so that friends who didn’t visit the center would still be able to learn. In this way, the airplane study even got children engaged in literacy activities.

The cover of the book children wrote and illustrated about how to make a paper airplane

To help children master all the tricky folds involved, we incorporated shapes, an important Pre-K math standard, into the process. At each fold, we asked the children to identify and count the shapes in their soon-to-be planes: “Now fold it in half - how many rectangles are there?”

Soon enough, everyone had their own paper airplanes, which they flew through the classroom the rest of the day. Conversation started buzzing about whose plane flew the straightest or the fastest or the furthest. This was it - our way into a unit on measurement.

Children working together to make paper airplanes for everyone, A student working on measuring and units of measurement with connecting cubes and popsicle sticks

We started with a conversation about how we could answer their question, Whose plane can fly the farthest? The children generated ideas that got at the heart of measurement: “count in a straight line,” “see how long,” “put two things next to each other” and compare. We were able to see what children already knew about measurement, and start to create experiences for them to build their skills, such as measuring different lengths of tape with various manipulatives (and recording the number) and discussing precision through reading Ants Rule by Bob Barner and measuring different bugs (“you have to push the cubes together - they have to touch!”).

The start to a classroom wall documentation recounting how the work emerged

After spending many days practicing using different measurement tools and thinking critically about how to understand number relationships (e.g. if the number is bigger, then the object is longer), the children were ready for the big event: the fly-off. The children grabbed their paper airplanes and we all headed into the school gym to see if we, now armed with new knowledge and skills to answer our driving question “How can we find out how far the planes flew?” could find out how far our planes could fly and whose plane could fly the farthest.

One small group of children working on the fly-off

Ultimately, the children weren’t interested in finding out whose plane flew the furthest - they wanted to throw their planes and use their developing measuring skills to measure their own plane’s journey. It didn’t matter - what mattered was that they were invested in the learning and engaged in the mathematical concepts involved. The idea had emerged from “one of their own” (a child, rather than the teacher), they had generated the target question for our study, and had, in the end, successfully built up new ways of approaching the concept of measurement.

This initial study led us to studying other modes of transportation, creating stories and books about our journeys on boats, trains, and bicycles, and expanding our understanding of measurement by considering the more abstract concept of time.

Knowing the Pre-K math standards well enabled me to see an authentic opportunity to include complex math content related to the children’s interests. Mathematical concepts can be easily incorporated into so many PBL units. Shapes, ordinal numbers, measurement, patterns… If you hear an idea and feel like there might be math hidden inside, pull out your math standards and sketch it out in a concept web (the idea at the center, and possible learning strands branching off). You may be surprised how many learning opportunities you find! A classroom culture of collaboration and co-construction of knowledge empowered the children, and me as their teacher, to create a meaningful mathematical learning experience for all of us.

Lisa Goddard is a Reggio-inspired curriculum coordinator and pre-k teacher in Boston, MA. She is a graduate of Brown University (BA), University of Edinburgh (MS), and Boston University Wheelock College of Education & Human Development (MEd). When she isn’t in the classroom, Lisa loves running, walking her dogs, traveling, and painting.