Mapping Our World: A Study of Identity, Place, and Rights

As a founding first grade teacher at The Croft School in Boston, Massachusetts, I’ve realized that the most magical learning experiences happen when students themselves become the “founding” teachers. This was exactly the case last year, during our Project Based Learning (PBL) unit on mapping, when students took the idea for a final public product into their own hands.

At our school, The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is a topic of learning and discussion on World Children’s Day (November 20). The CRC includes fifty-four civil, political, economic, social, health, and cultural rights of children. Countries that have ratified the CRC agree to ensure these rights for all children. A great video to introduce children to the CRC is: We all have rights (UNICEF).

In the winter of 2022, our class engaged in a short study on rights - connected to The CRC during our mapping unit. The driving questions for this portion of the unit included: What is a right? Where in our community can we fulfill (get) these rights? What makes these places and businesses unique?

While having a public product wasn’t part of the plan, students weren’t ready to move on without sharing their learning. They decided to create 3D representations of places in our community that provided access to the rights most important to them. This became the last-day-before-winter-break installation we called the “Museum of Rights.” (While the timing felt stressful for me as a teacher, the looming deadline of winter break actually motivated the students in an impressive way!) The museum included a large map of our local Boston neighborhoods, marked with specific points that identified each place included in our museum - examples including: The Museum of Science (right to play), The Embrace (right to protest), and the Rocky Mountain Spring Water Company (right to clean water).

While I appreciated the student-led decisions that shaped this project, I wanted to be more intentional the second year. So I collaborated with my first-grade colleague, Marissa Murphy to combine two previous units—identity and mapping—to create “Mapping Our World: A Study of Identity, Place, and Rights.”

Planning, Un-Planning, and Re-Planning: Improving and expanding the “Museum of Rights”

Throughout the replanning process (or perhaps I might called it a “improvement and expansion process”), we noticed that identity, place, and rights could combine to create a meaningful, justice-oriented mapping unit. Over 15 weeks, we broke the unit into smaller chunks: self-identity, group identity, rights, and mapping. Our guiding questions were:

Self-Identity: What makes me unique? What is important to me?

Group Identity: What groups am I part of in my community? What is important to these groups?

Children’s Rights: What is a right? What rights are important to me and my groups?

Mapping: What places in my community provide access to these rights? Does every child in Boston have a similar experience?

Children’s Rights: What is a right? What rights are important to me and to the groups I am a part of?

We used two student-generated lists as anchors for the mapping portion. To start thinking about rights, we utilized maps that connected to the lists (maps of zoos to represent our appreciation for animals, maps of beaches to represent our appreciation for oceans, maps of Legoland to represent our appreciation for toys), and worked together to sort the maps into two categories: wants and needs.

The discussion following this activity was fascinating. We concluded that our wants and needs were unique. A map of “Cape Cod Beaches” could be a need for one person (“My family lives there, and I need to visit my family”) - but a want for another person (“The beach is a fun place to go, but I don’t need to go there to survive.”) We also concluded that most of our maps represented places we might want to visit, but don’t need to visit “to survive.” We felt confident about our conclusions.

This was the perfect timing to reflect on these wants and needs from a different perspective. We were inspired by a colleague (Lisa Goddard) to include children’s rights as a topic in our mapping unit. After exploring a child-friendly version of the CRC, we looked back at how we sorted our maps into wants versus needs and concluded that almost every map we had sorted could be considered a place that fulfills a right for children - in other words a need.

Click here to download this image as a PDF

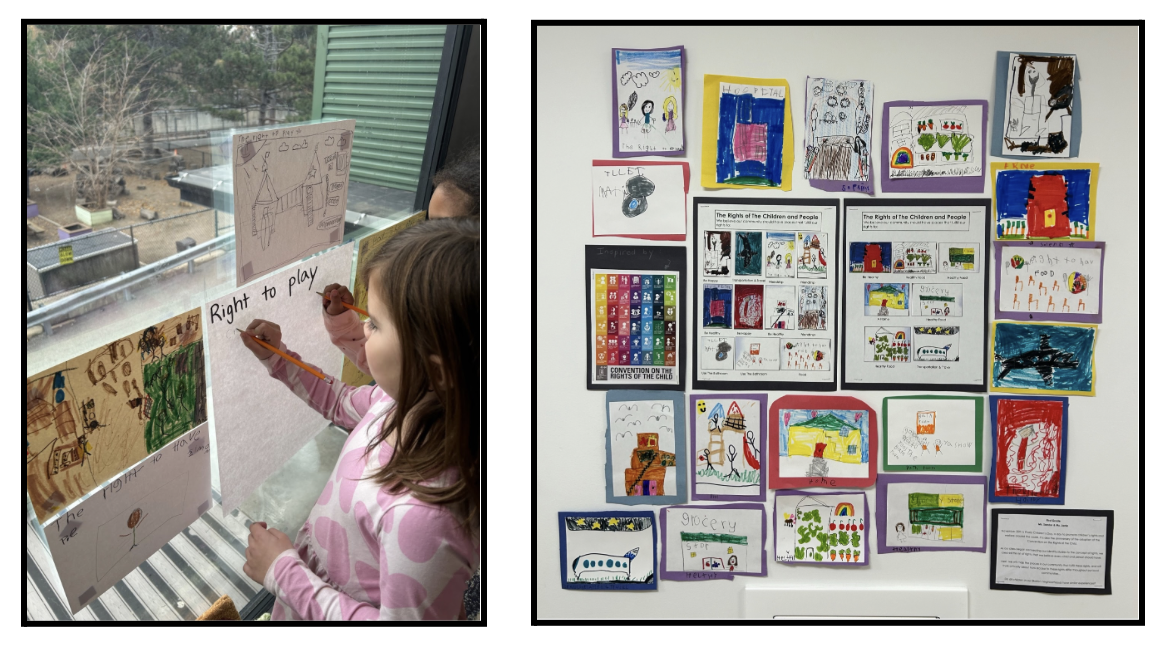

From there, students chose the CRC rights that resonated most strongly with them, and brainstormed places in our community that help fulfill those rights. We discussed places where children can access books, doctors, healthcare, healthy food, transportation, a home / shelter, public bathrooms, and the obvious favorite: access to the right to play. We took the time to illustrate these ideas, which ended up becoming our own unanticipated version of the CRC (another unexpected perk of this “improved and expanded” unit).

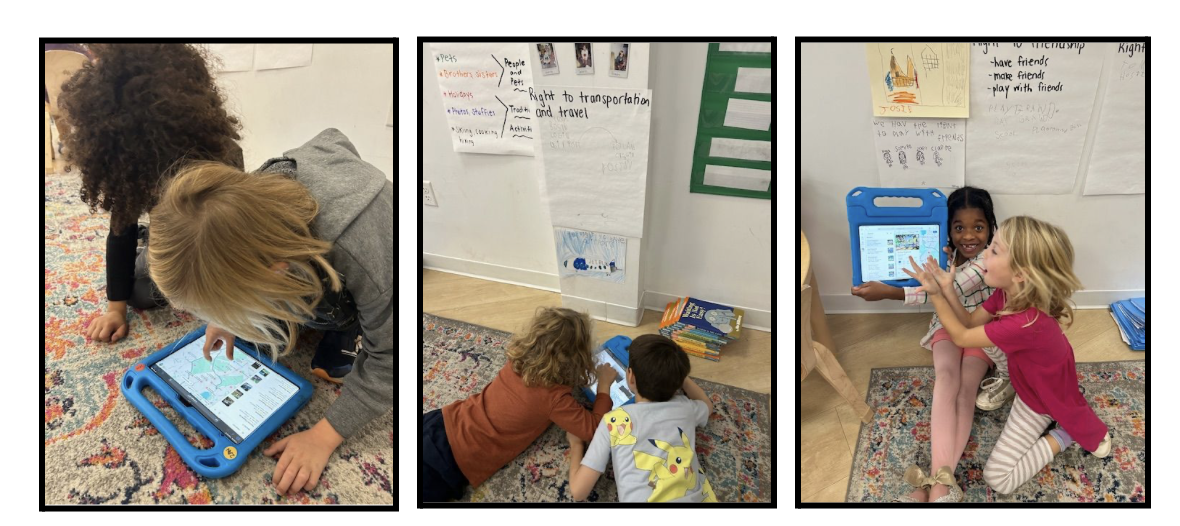

Finally, we continued working with various rights of choice (the right to play, the right to have a home / shelter, etc.). We used Google Maps to find additional places that could fulfill these specific rights, and learned more through websites, articles, and customer reviews. It was enlightening to see the progression of vocabulary and language that we used while searching, because it perfectly matched the directions we decided to go with our projects. For example, “places to play” became “playgrounds,” and “food” became “healthy restaurants,” and “friendship” became “parks and playgrounds.”

Mapping: What places in my community provide me access to these rights? Does every child in Boston have a similar experience?

Once students had researched places fulfilling their chosen rights, I marked these on Boston neighborhood maps. (For example, if a student wanted to represent playgrounds for the right to play, I marked playgrounds on the map.) These maps were the provocation for our final question: Does every child in Boston have a similar experience? We quickly observed that some neighborhoods had many playgrounds, while others did not. Hospitals were plentiful downtown, but became more dispersed in the outer neighborhoods. We then used our hand-drawn images from our own CRC (scaled down to mini-size) to mark areas on our neighborhood maps that could benefit from additional access. Using vellum paper overlays a reader could flip from the actual (teacher created) map of playgrounds, to the student-generated map that identified where there should be more playgrounds for children.

Since this final exercise didn’t necessarily account for restrictions such as limited space, zoning restrictions, and other realistic challenges that would limit playgrounds from simply “popping up” at every corner, I also created a list of “pondering questions” for each right, and we discussed these together. For example, “What will a neighborhood do if they don’t have room for a playground?” These questions led to a rich discussion, concluding with “the neighborhood can maybe find a business that isn’t doing good for the people, and replace it with a playground.”

A Celebration of Learning: Sharing our process and products with families

To share our work publicly, we put each element of our projects into a book. The book not only showcased what we had learned about maps, but also highlighted the accessibility of rights in our neighborhoods, and highlighted the proposed areas in need of more equitable accessibility. Since each book focused on one specific right, readers could explore the variety of rights researched by our class. We shared these public products during our learning celebration, which was a culmination of our experiences throughout the entire unit, from self and group identity, to children’s rights, to mapping. Students even practiced asking their pondering questions to others, so that they could be utilized as discussion prompts with families during the event.

Next Year: Improving and Expanding (Again): Reaching for the delicate balance

Next year, I’d like to broaden the range of rights that my students choose to study during this project. While The CRC includes fifty-four rights, my students often gravitate toward familiar rights such as “play,” or “medical care.” Maintaining the balance of pushing students to research something new - while still allowing them to have choice and ownership in their decisions is delicate, but this also encourages me to strive to improve and expand the unit.

By the end of this unit, students learned how to use maps as research tools for critical thinking and reflection about children’s rights. They learned to appreciate the places in our communities that provide access to rights, and proposed solutions to inequities. This unit showcased the depth maps can offer, far beyond simply showing routes from Point A to Point B. As communities evolve, this unit can continue fostering justice-oriented thinking and social awareness in young learners.

Lisa Sander is a passionate educator who is currently a founding first grade teacher at The Croft School in Boston, MA. She appreciates teaching in environments with a strong sense of community and a commitment to student-centered learning. To create balance in her own life, she enjoys running, traveling, and reading in her free time.