Investigating the Everyday: Planning a Reggio Emilia-inspired Science PBL Unit

The Reggio Emilia Approach and PBL

When I first visited the early childhood centers in Reggio Emilia, Italy, I was transported to a culture where children are the primary decision-makers in their own education. In the town of Reggio Emilia, evidence of the children’s work is everywhere. From the whimsical murals they painted on walls of pedestrian walkways to drawings of trees displayed around Reggio’s public parks, everything is thoughtfully designed by the children. Even the town’s theater even has a stage curtain designed by school children.

As an early childhood educator, I am guided by the educational philosophy of Reggio Emilia that all children are active citizens who are capable, curious, and rich in potential (Gandini, 2003). In Reggio Emilia, they practice a unique approach to progettazione or project-based learning (PBL). Carlina Rinaldi, past president of the Reggio Emilia municipal schools, expressed that progettazione is a dynamic process, a journey that “means being sensitive to the unpredictable results of children’s investigations and research” (Rinaldi, 2005, p.19). In Reggio, teachers are primarily researchers who work in partnership with their students, supporting (and often challenging) their thinking on various topics of interest.

PBL and the Reggio Emilia Approach follow similar pedagogical styles but have some distinct nuances. The Reggio Emilia Approach exemplifies the PBLWorks model for Gold Standard PBL. In Reggio projects, driving questions are initiated by either the child or teacher. There is also much voice and choice involved as both the teacher and students make agreements on what to further research, what resources will be helpful to answer their question, as well as who should be contacted to support their sustained inquiry. Part of what has made Reggio Emilia internationally famous is their expertise in elevating the status of children through extensive public exhibitions of student work.

Some nuances that give the Reggio Emilia Approach its distinct style is the emphasis on using artistic mediums to construct knowledge and the careful documentation of student learning that occurs throughout a project.

By integrating PBL with the Reggio Emilia Approach, the teaching emphasis shifts to projects focused on everyday objects and events based on children’s direct experiences. What some may consider a mundane topic such as rain puddles, educators in Reggio see it as worthy of an in-depth investigation. There is value in “defamiliarizing” everyday experiences for project work (Katz, 1998).

I am excited to share my experience with defamiliarizing the topic of ants with my TK/K students through a Reggio-inspired PBL unit.

Inspired by Ants!

One of the PBL goals that I had for the 2019-2020 school year was to support my TK/Kindergarten students’ research around the life science concepts outlined in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). My school has multiple outdoor classrooms, and I leveraged these spaces to help students “unpack” everyday encounters within their natural environment.

One September morning, as my students made their way to our outdoor picnic benches for snack time, I heard an almighty shriek coming from two girls crouched underneath one of the benches. The girls pointed to a long trail of ants, crawling over pieces of scrap food that had been accidentally dropped. It wasn’t long before almost my entire class was kneeling beside the ants examining them and asking questions such as: “Where are they coming from?” “Why are they eating our snacks?” “How do they eat?” “Where is their own food?” Since the class was so captivated by the ants, I felt that this would make a great topic for a PBL unit and would naturally address many NGSS life science standards such as: K-LS1-1 Use observations to describe patterns of what plants and animals (including humans) need to survive. It was interesting to reflect on how something so commonplace such as ants, would suddenly become an extraordinary part of my students’ daily life at school.

Observing and Responding to the Children

To help me assess whether this would be a worthwhile topic of investigation, I spent several days observing and documenting my students’ ongoing interest in ants. I held a class meeting showing photos of the students at snack time looking for “ant homes.” It is standard practice in Reggio Emilia project work to document children’s actions through photographs or videos. This documentation is frequently revisited with children to reignite their interest in what they observed. The photographs that I showed them brought back memories of their excitement over the ants, and I began asking: “What do you know about ants?” and “What more would you like to find out?” Their responses and questions played an essential role in planning future lessons/activities for the project. We agreed as a class to focus on a primary Driving Question: “How do ants live?” to help guide our inquiry.

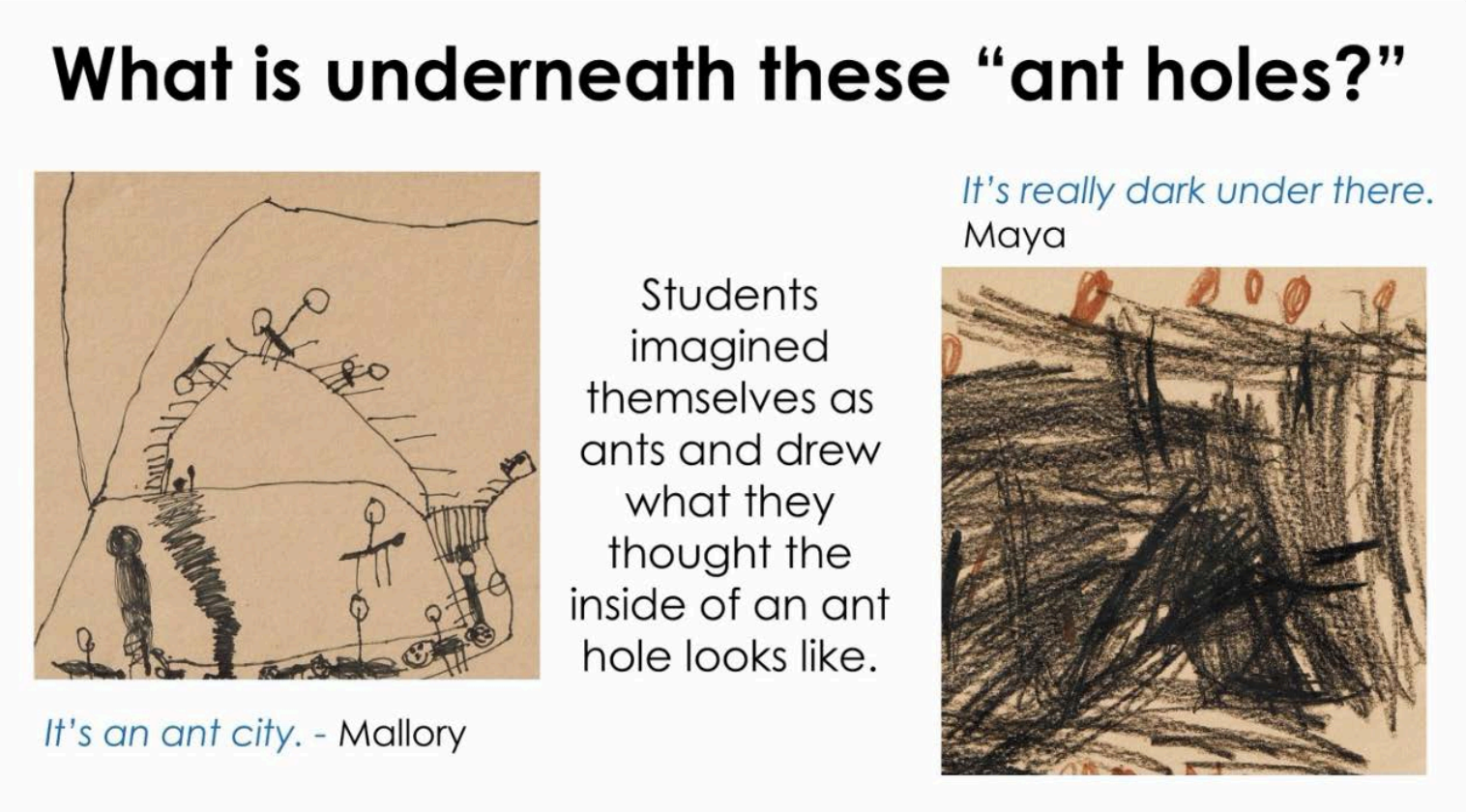

I invited students to draw what they thought was inside the “ant holes” they had discovered. In Reggio Emilia, projects typically start with a verbal and graphic exploration (Rankin, 1998). Reggio educators engage their students in collaborative conversations and encourage them to draw about the topic in order to gauge their interest.

Using the Hundred Languages to Deepen Investigation

A sub-topic of our project focused on ant habitats. I purchased a small desktop ant farm so students could observe in real-time the social interactions of live ants and how they construct tunnels. We also read non-fiction books and viewed science videos about ants to help us answer questions that arose from our observations. Students had a great deal of voice and choice as we used what Reggio Emilia educators describe as the “Hundred Languages” which is a metaphor for any material, medium, or technology to construct an understanding of the world around them. We painted a collaborative mural to illustrate the construction of an ant colony. Students also sculpted models of ants to learn about their anatomy and took photographs in the garden from an ant’s perspective.

During the final stages of the project, we reflected on our learning by creating a class book where we drew and wrote facts about ants. We displayed the book and other products created during the project at a public exhibition for our local community.

Conclusion

Like educators in Reggio, I find value in making everyday experiences an integral part of Project Based Learning. I encourage you to pause, listen, and document what captivates your students’ interest whether they are on the playground, on a class nature walk, or during free play. You will be surprised at the number of unexpected topics that can be “defamiliarized.” To help launch your own Reggio-inspired journey, I recommend reading Inviting Children into Project Work and viewing Reggio Emilia Long-Term Project Documentation Video.

You can view the documentation photo book of the ant project here.

For the past seven years, Ryan Kurada taught Transitional Kindergarten (TK) through 1st grades at University Elementary School in Rohnert Park, California. He enjoys planning and implementing projects with STEAM content inspired by student interest. Ryan currently serves as a Science Coordinator at the Sonoma County Office of Education and is an adjunct faculty member at Sonoma State University.

References

Gandini, L. (2003). Values and principles of the Reggio Emilia approach. Insights and inspirations from Reggio Emilia: Stories of teachers and children from North America, 25-27.

Katz, L. (1998). What can we learn from Reggio Emilia. The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach—Advanced reflections, 27-45.

Rankin, B. (1998). Curriculum Development in Reggio Emilia: A Long-Term Curriculum. The hundred languages of children: the Reggio Emilia approach--advanced reflections, 215.

Rinaldi, C. (2005). Is a curriculum necessary? Children in Europe, 9, 19.