Curiosity, Exploration, and Creation: PBL with 3 & 4 year olds

The Learning and Belonging (LAB) School is part of the College of Education at the University of Montana in Missoula, Montana. We are in our second year of PBL implementation with 3-5 year olds in three classrooms.

We’ve learned so much in just two years and wanted to share the experiences of one of our teachers, Danielle Bailey, a reflective educator who has been implementing projects in her classroom of 3 and 4 year olds. We hope that by sharing some of the innovative practices that she uses to meet the needs of her youngest learners as they engage in PBL, we will continue to help to dispel the misconceptions that young children are not capable of fully participating in PBL.

PBL with Three-Year Olds: The Importance of Open-Ended Play and Learning

Danielle’s learner-centered classroom utilizes a variety of play and inquiry-based approaches to instruction, creating the perfect foundation for project based learning. Like many early childhood spaces, Danielle’s class has a variety of centers that allow opportunities for the learners and teachers to engage in exploration and rich conversations. Each center area is thoughtfully designed to support a problem, question or project milestone. Through conversations, teachers are able to gain information about what learners are curious about. Teachers listen intently to know when to jot down a conversation or take a picture of the learning in action. This work provides opportunities for students to share what they notice and are learning with teachers who are then able to make adjustments to the project in real time to support students’ curiosity.

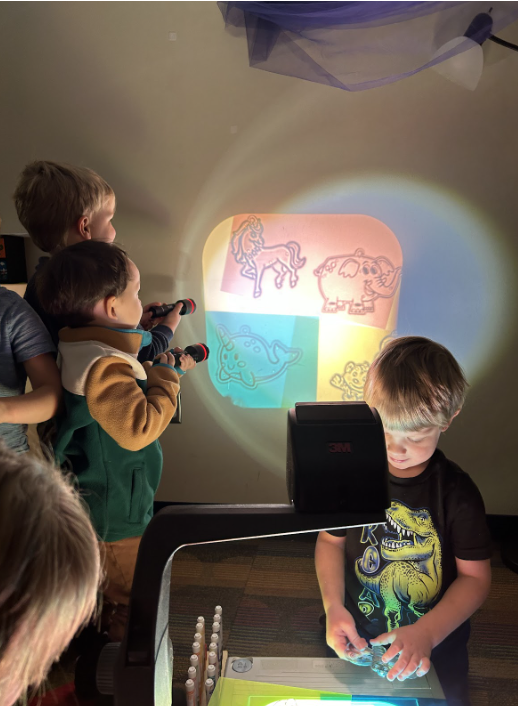

In Danielle’s classroom you will also routinely see adults on the ground, sitting at tables, or kneeling at child-level to have conversations that are child-driven. The goal is always to facilitate conversations that deepen learning through play. For example, in a project that focused on light and darkness, Danielle set up a sensory bin of water and green glow sticks. Flashlights were also available throughout the classroom. As children explored and moved items to different areas of the classroom, some flashlights even found the water. Whenever children are conversing during play, the teachers use clipboards to document what children are saying and who is saying it. Additionally, Danielle takes a plethora of pictures to analyze later. She is constantly looking for images that show children engaging with the documentation around the room or engaging in play related to any project milestone objectives. By doing this she is able to formatively assess where learners are within the context of the project goals.

Danielle is careful to take the collected documentation and formulate questions based on the children’s curiosities. She creates a chart that includes children’s names, their statements, and the wondering/question she has formulated, often with photos for support. Danielle and her co-teacher share the questions with the learners, modeling how to ask questions. For example, If Danielle hears a statement that really reflects a question, she might say, “Lily said…That means she might be wondering….”

Planning for a “Yes Environment”

Planning is the key piece that allows Danielle and her co-teacher to follow, engage, and scaffold the playful learning that occurs daily in the classroom. To support thoughtful, intentional planning Danielle worked through her PBL planning outline. The team focused on anticipating the students’ questions, identifying milestones, and weaving together learning experiences seamlessly.

An essential part of the project planning process was figuring out how Danielle’s Loose Parts philosophy (Nicholson, 1972), and a “Yes Environment” (Elkins, 2019) fit with PBL. In this type of environment, a teacher expects the children to move the materials throughout the classroom space. For example, the flashlights that begin the day in dramatic play often leave that area to be used for different purposes as the learners are exploring, repurposing, and/or being curious about their world. As part of this Loose Parts philosophy, Danielle must also anticipate where the project might go so she can ask open-ended questions, add materials slowly and purposefully, and be prepared for surprises. One such surprise emerged during the project about light when Danielle and her co-teacher were playing and investigating light with the children. They found students were also interested in solar panels. This was not part of the predicted need to know questions or anticipated prior knowledge. Danielle was excited to gain this insight and was able to add solar panel investigations into the project plans based on students’ interests.

Throughout this experience, teachers were listening intently to know when to jot down a conversation or take a picture of the learning in action. For this specific project, Danielle and her team set the stage for exploration with a sensory bin of water and green glow sticks. Flashlights were also available throughout the classroom. As children explored and moved items to different areas of the classroom, some flashlights found the water.

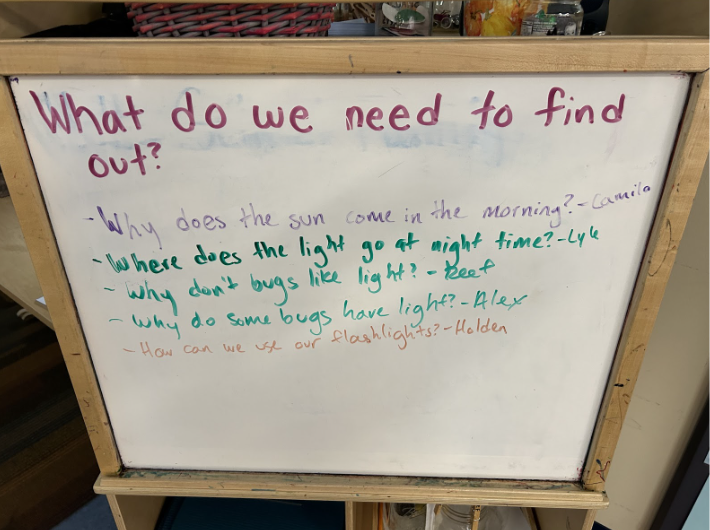

Scaffolding Student Questioning and Playful Inquiry

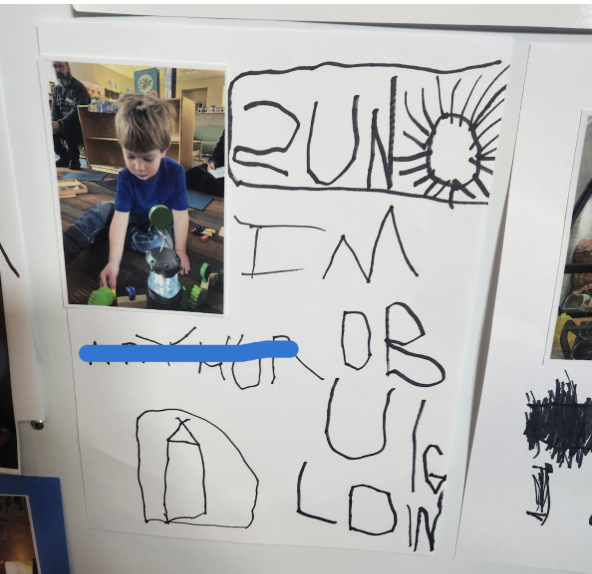

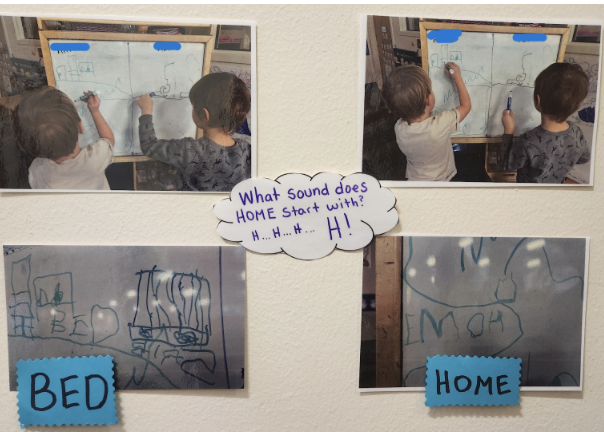

During this most recent project, initial attempts to elicit project “Need to Know” questions in the whole group, small group, and individually were not as successful as she’d hoped, so Danielle decided to scaffold the question-generation process. While young children ask lots of questions when playing, formatting questions on-demand is not typically part of their skill set. Danielle took this knowledge about children’s questioning and curiosity during play and formulated new processes for documenting learners' curiosities. Part of this new process was to add blank speech bubbles next to classroom photos. The intention being to teach children to use these speech bubbles to make their own captions for the work they are doing. This skill was practiced and reinforced during small group time, as seen in the pictures below.

A key aspect of Project Based Learning is making the learning visible, so Danielle works to ensure that project documentation is accessible and engaging. Upon realizing that she might be robbing the children of opportunities to create and be involved in the learning process, she began to make anchor charts with the children. She also began placing charts in specific, intentional areas of the room, like the block area, and modeled how to use them throughout the day. Since making these changes, Danielle has seen the children reference and use the charts more often with each other.

Reflections

Reflecting on this process, Danielle and her team learned that 3 year olds come ready with curiosity, exploration, and creation. It is our job, as teachers, to prepare an environment where children find themselves as capable creators of their own learning through utilizing PBL. Moving forward, Danielle is excited to continue to listen while children play and guide them in the formation of big questions and how to answer them.

The project wall after launching the Light PBL unit with examples of the thinking the children are doing.

Anna Puryear is an early childhood doctoral student at the University of Montana. She was a co-teacher at the LAB school last year and is now serving as a coach and researcher. In her 23 years of experience in education Anna has developed PBL units for various grade levels and enjoys engaging teachers and children in this empowering practice. When not studying and engaging at LAB she enjoys reading and watching her children love what they do.

Danielle Bailey is an Early Childhood Clinical Specialist and Adjunct Professor in the Learning and Belonging School at the University of Montana. She is the Lead Teacher in our Morning Preschool classroom and works closely with our Early Childhood college students. Danielle has always been passionate about Early Childhood and the impact a supportive environment and adults can have on our earliest learners. When not in one classroom or another, Danielle enjoys spending time outdoors with her family and noticing the very first signs of Spring.