Tutoring for Engagement: Integrating Project Based Learning to Boost Literacy Skills

When I decided to tutor students for the summer in reading and writing, I also decided to include Project Based Learning (PBL) components. Why PBL? In a word: engagement. Research indicates that deep reading engagement promotes reading achievement (Barber and Klauda, 2020). PBL is one means that can facilitate reading and writing engagement, even for students needing extra support. Early elementary students need the tools to begin their literacy journey and to feel motivated to continue it. This motivation is absolutely imperative at any time, but especially when asking students to engage in school work during the summer.

Another reason to choose a PBL focus was to maximize instructional time. Integrating literacy is commonplace with many subjects. In the case of one student, I also wanted to incorporate social-emotional learning. Time is usually more limited in a tutoring setting than in a regular classroom environment. PBL is ideal for making the best use of instructional time via interdisciplinary learning, and it’s effective. A study by Nell Duke and colleagues (2020) showed that students who engaged in a social studies and literacy PBL project gained 2-3 months of informational reading skills compared to students in a comparison group, and 5-6 more months of social studies learning.

Goal One for my summer tutoring was to help each student find a project that would be of high interest to them, and give them authentic reasons for reading and writing. To help my young students find a passion project, I asked caregivers to share the literacy skills students needed to work on, as well as students’ favorite characters, activities, and topics. During our first meeting, I asked students to tell me more about what they enjoyed learning about. I used this information to make some suggestions about possible projects. Typically, in a PBL project, there is an entry event to spark students’ curiosity about the upcoming project and learning goals. In this case, the entry event was finding out the students’ interests.

Student Driven Learning Through Authentic PBL

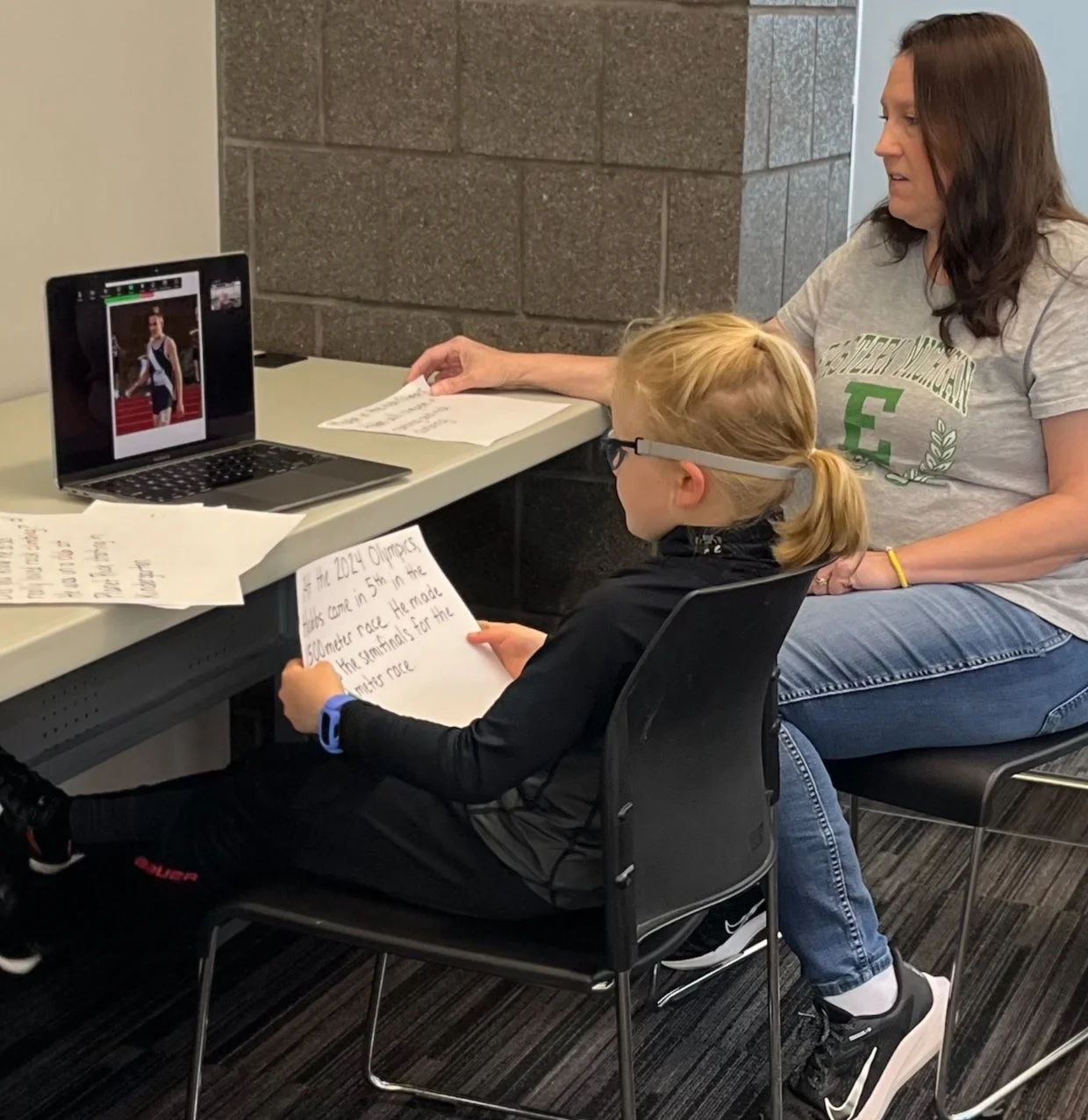

Ryanne, a rising second grader, was working on speaking and listening skills, reading fluency, and developing ideas into a writing piece. As a big sports fan, she decided to make a sports report video that I could show to upcoming first graders about a local runner who made the 2024 Summer Olympics. I talked with Ryanne about the upcoming Summer Olympics as an entry event. Caihong, also a rising second grader, loved unicorns and drawing. While she needed work in reading fluency and developing her writing ideas, she also needed help with initiating interactions with peers and using calming strategies when feeling overwhelmed. After explaining what a social story was, and pointing out an example that I knew she had read before, we launched the project. I asked Caihong to write and illustrate a social story for my first grade classroom. In PBL, the next step would typically be to develop a driving question. I co-created the driving questions with students by giving the sentence starter, “How can I write/make a … (news report, social story)?”

Caihong works on the text of her social story

Now that each student had an authentic purpose for reading and writing, we began working on another part of the PBL process: creating “Need to Knows”. In other words, we worked together to determine what the student would need to find out in order to complete their product. For example, Ryanne, who had decided to make the news report, determined that she needed to know more about the Summer Olympics running events and about runner Hobbs Kessler. Caihong decided she needed to know about different types of social stories so that she could decide what kind she wanted to write. (I made sure to find some models that included unicorn characters).

An important aspect of PBL is collaboration. Given the fact that my tutoring was one on one, peer collaboration wasn’t possible. However, one project did lend itself to using a local expert collaborator. Local Olympic contender Hobbs Kessler had been the student of a fellow teacher, so I arranged for a Zoom interview between Kessler's former teacher and my student. The benefits of this were two-fold: the student gained authentic practice with speaking and listening skills, and got firsthand information from an expert.

Ryanne reads from cue cards while recording her video

Although peer collaboration wasn’t part of these projects, a peer audience was chosen for each project, adding important authenticity and relevance. Both projects will be shared with my future first graders, this coming school year and beyond. Caihong’s social story will be a part of our classroom calming area, and Ryanne’s video will be shown as a part of our hopes and dreams models at the beginning of the year. Since Ryanne and Caihong both attend my school, these first graders are their younger peers.

Because of its focus on authenticity, and the natural inclusion of student voice and choice, students found the learning presented in a PBL format to be very engaging as evidenced by a written reflection completed after the project. Caihong said “it made it (tutoring) more fun to do a project” and Ryanne started planning her “next video” as soon as the project was done. As a teacher, I also found the tutoring to be more interesting and fulfilling as I got to learn along with my students about their chosen subjects.

Ryanne is excited for others to see her video.

Caihong is proud to have written a book.

Tips for incorporating PBL in a tutoring setting:

Be conscious of a more limited time frame. During the regular school year, you may be able to spend a little longer on the project. Tutoring time tends to be a bit more finite. For example, these two students each met with me once a week for 30 minutes for 8 weeks. You will need to plan carefully to accomplish the project goals.

Be sure to share models of projects with your students. Caihong studied different social stories, and Ryanne watched carefully selected news reports about sports.

Have some ideas ready to provide choices to your young students, both of projects and possible authentic audiences.

Look for opportunities to collaborate with peers and subject experts (if you want to do PBL regularly, it can be helpful to make a spreadsheet with willing subject expert information).

*All names have been changed to protect the privacy of the students.

Beth Lafferty is a first grade teacher at A2 STEAM, a public K-8 school in the Ann Arbor Public School District. She also co-leads the literacy committee at her school, and was a member of the teaching team that facilitated the school history project with first graders, profiled here on our ECPBL blog.